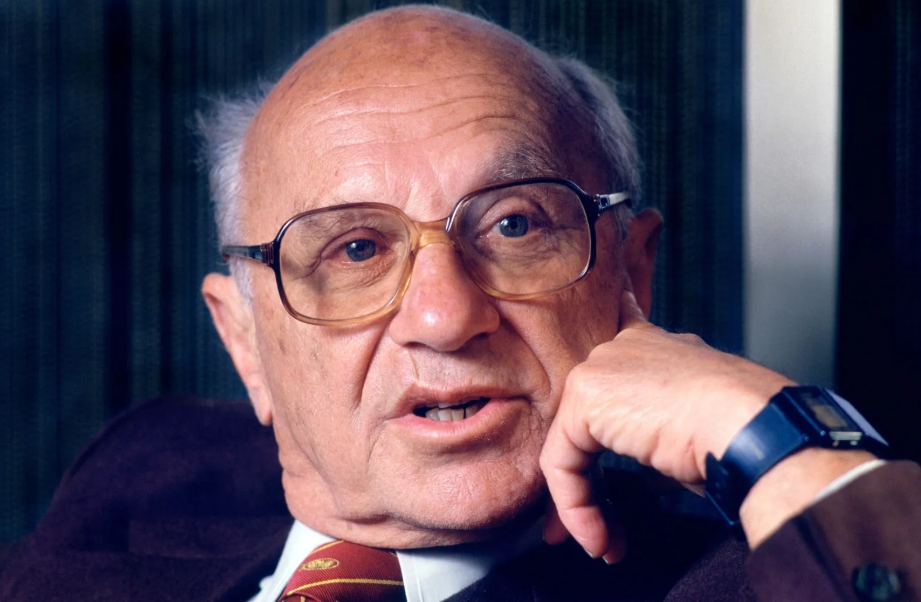

Headline: Milton Friedman Is Still Running the Economy—From the Grave

Dead Economist, Live Ammo: Milton Friedman’s Ideas Are Still Killing Us

Eighteen years dead, Milton Friedman still signs the checks. Every tax cut, every gutted regulation, every excuse for inequality has his fingerprints on it. His ideas are still killing us.

The University of Chicago economist didn’t predict the 2008 financial crisis—he couldn’t, he died two years before it hit. But the people who did see it coming—Raghuram Rajan, Nouriel Roubini, Dean Baker, Robert Shiller—were treated like eccentrics shouting at clouds. Friedman’s followers were too busy polishing their Nobel Prizes and congratulating themselves for inventing “efficient markets” to notice the smoke pouring out of the engine. The crash wasn’t a surprise. It was the natural endpoint of the economic theology Friedman spent decades preaching.

He sold Americans a beautiful lie: that markets were natural forces, like weather or gravity, instead of human constructions rigged by whoever has the fattest wallet. Greed wasn’t just good—it was mathematically optimal. Selfishness became science. Capitalism and Freedom became the bible for every bean counter who wanted to call avarice a virtue. Friedman handed them indulgences. Go forth, he said, and maximize your profits—God, or at least Milton, smiles upon you. Government? Just a meddlesome hall monitor.

When Paul Volcker took monetarism for a test drive in the early ’80s, the economy coughed, stalled, and left nearly eleven percent of Americans without jobs. Then came the savings and loan crisis, where deregulated banks set fire to depositor money and taxpayers held the extinguisher. By the time his disciples finished dismantling Glass-Steagall, Wall Street could turn mortgages into poker chips and bet the house—yours.

By 2008, Friedman’s most devout pupils were running the show. Ben Bernanke and Alan Greenspan—both committed believers—stood there like magicians whose rabbit had just eaten them. Greenspan, fresh from his long reign at the Fed and long celebrated as the Maestro, had just published The Age of Turbulence, where he dismissed the idea of a national housing bubble, echoing National Association of Realtors economist David Lereah’s “real estate is local” fairy tale. Lereah had written Why the Real Estate Boom Will Not Bust, assuring buyers there was no such thing as a housing bubble. They weren’t just wrong—they were wrong with absolute confidence, the most dangerous trait Friedman ever handed down.

Turns out financial systems aren’t just about money supply. They’re about trust. And when trust collapses, theory won’t even buy you lunch.

Friedman’s real weapon wasn’t his math—it was his certainty. He produced a generation of economists who treated their models like scripture and human suffering like background noise. They landed in the Fed, the Treasury, and every major bank. They engineered derivatives so complex they made nuclear reactors look user-friendly. They swore banks would regulate themselves. They treated the economy like a physics lab, forgetting there were actual people trapped in their experiments.

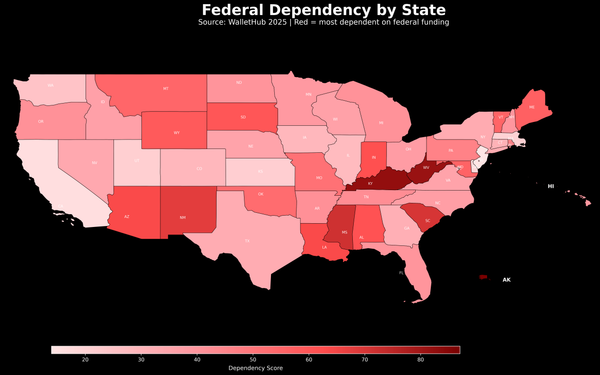

Here’s what they never admit: there’s no such thing as a free market. Every market runs on rules—property rights, contract law, bankruptcy courts, currency systems—and those rules are made by governments. The question isn’t whether government shapes markets. It’s who it shapes them for.

Adam Smith’s The Wealth of Nations—the book they name-drop like it’s a backstage pass—wasn’t about money. Money’s just an IOU. Smith was talking about real wealth: the resources and production that keep a nation alive. Grain in the granary, iron in the foundry, ships in the harbor. Friedman’s trick was to treat money as the measure of everything, so he could declare the market “free” while resources were being hoarded or stripped bare. In Smith’s world, clear-cutting a forest to juice quarterly profits was vandalism. In Friedman’s, it was efficiency.

Friedman’s “free market” wasn’t free. It was bought and paid for by the people who profited from it—and we’re still picking up the check. It was a gated community. You weren’t invited.

The 2008 crisis cost trillions, erased millions of jobs, and left a crater in the middle class. We clawed our way out over a decade, and just when we caught our breath, his ghost whispered, Cut taxes again.

Every time a politician says tax cuts pay for themselves, that’s Milton. Every time a regulator decides banks can police themselves, Milton again. Every time someone says inequality is just the price of freedom, you’re hearing him through the grave dirt. You can see him in private equity firms gutting hospitals and selling off the buildings while patients wait on gurneys in hallways. You can see him in oil companies raking in record profits during an inflation crisis, then hiking dividends instead of cutting prices. You can see him in billionaires paying lower tax rates than their assistants, shrugging and calling it the market rewarding hard work.

The bean counters adored him bcause he made greed respectable. They built think tanks in his name, handed out medals, and taught his gospel in classrooms. They made sure his ideas would outlive him—maybe outlive all of us.

But ideas have consequences. And Friedman’s consequences keep compounding, like interest on a debt we’ll never pay off. The man who said there’s no such thing as a free lunch somehow missed that there’s also no such thing as a free market. He gave greed a diploma, and the bill’s still coming due.

We’re not living in his legacy—we’re trapped in his balance sheet.