More Ads

way too many

My friend Dave thinks I write about PrumpTutin too much. He’s not wrong. So today, I’m trying something different. I’m going to focus on the most minor matter I can think of. Something small. Almost silly. A little rant—not about democracy or disaster, just about the everyday things that somehow manage to drive us up the wall. Think of it as a friendly break. A soft detour. Because some days, the best we can do is notice the absurd stuff and laugh at it together.

It’s 2025, and the average household is now paying around $60 a month for streaming—not for ad-free entertainment, but for the privilege of watching ads across multiple platforms.

It used to be a trade: you watched ads, but the content was free. Now, we’re billed monthly to endure more ads than ever—ads we can't skip, mute, or even separate cleanly from the shows themselves. Somehow, this passed for progress. I haven’t. I pay to be advertised to, tracked, and interrupted. It’s not a minor annoyance. It’s a swindle we’ve all been tricked into calling normal.

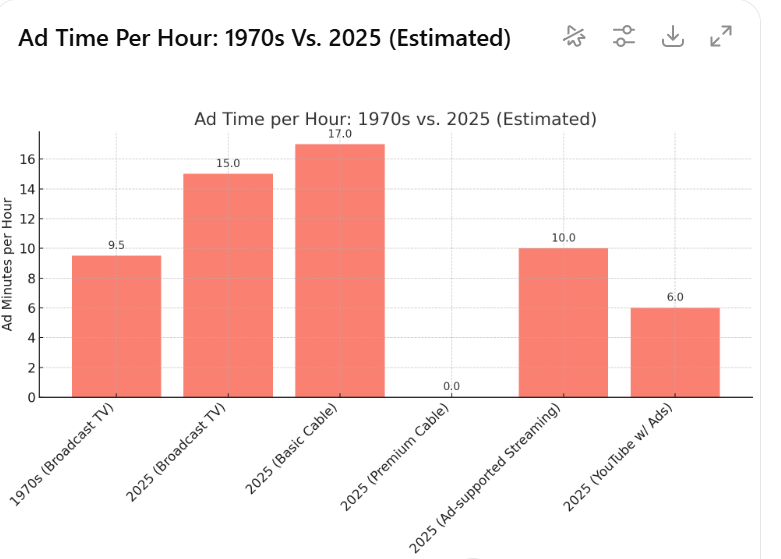

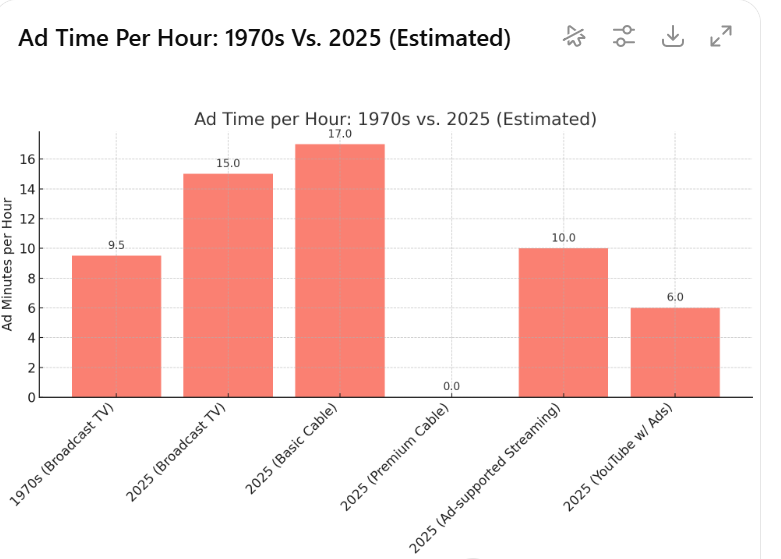

Television once meant mostly content, with a reasonable number of ad minutes—you turned it on, sat through clearly defined commercial breaks, and got right back to the show. In the 1960s, a one-hour series aired about 51 minutes of story and 9 minutes of ads. Nine minutes seemed reasonable—we understood that we had to pay for the show. And nine minutes gave you a chance to micturate. By the late 1980s, that had fallen to 48 minutes. By the early 2000s, most “hour-long” shows featured 42–44 minutes of content, with the rest filled by 16–18 minutes of commercials. For cable—which operated with fewer regulations than broadcast TV—those numbers sometimes climbed to 20–22 minutes per hour.

This slow erosion of content wasn’t noticed by most. But I noticed—and it made me mad. It wasn’t about missing a scene but about the growing sense that something important was being taken: our time, attention, and the integrity of the story being told. One minute I was watching a show. Next, I was watching a better-lit sales pitch. And almost nobody seemed to care

Cable's original selling point was simple: pay for better TV, and skip the ads. No interruptions, no commercial breaks—just uninterrupted movies and shows. That was the pitch that justified the monthly bill.

From the start, cable sold us freedom from ads. Then streaming came along and doubled down on that promise. Cable’s early premium channels—like HBO—offered uncut movies without a single ad break. Research shows that subscribers were willing to pay for access to commercial-free entertainment. When Netflix streamed onto the scene in 2007, its pitch was simple and clear: no ads, just the show. It was a bold move that positioned streaming as 'a clean break from the old TV model.

That promise was quietly broken—first by cable, then by the streamers who swore they’d be different. The economics changed. As production budgets soared and subscriber growth plateaued, streaming companies faced pressure from Wall Street to stop burning cash and start delivering profits. Licensing fees, original content, and tech infrastructure cost billions. Investors who once rewarded scale began demanding revenue—fast. As streaming costs ballooned, Wall Street redirected focus: what about subscriber growth? What about profitability? Lower-cost, ad-supported tiers entered the mix. Netflix joined the club in late 2022. Today, a third of its 300 million subscribers opt for ads—despite lower engagement, according to one study. Disney+, Hulu, Peacock, Max—they’ve all followed suit.

The intrusion isn’t just about quantity. It’s about invisibility. Hulu averages 4–5 minutes of ads per hour. Other platforms now run 8–10, and YouTube saturates nearly every video with pre-rolls, mid-rolls, banners, and unskippable ads. Monetization has become the rhythm—not the interruption.

More insidiously, advertising has woven itself into the content. Podcasts no longer pause for ads—they are ads. Hosts roll seamlessly into them, delivered in the same voice and tone. YouTube and TikTok creators have turned routines and stories into branded integrations glossily endorsed on cue.

Reality TV led the charge. The Apprentice didn’t just advertise—it was advertising. Every challenge was a corporate campaign for Burger King, Home Depot, Pontiac—ads presented as competition. Every shot, every phrase, every product placement was deliberate. The entire structure was built to showcase brands, with Trump as the ringmaster. It was wall-to-wall marketing—product plugs inside the show, and stacked traditional ads around it.

This model is now everywhere. Scripted shows feature logo-heavy products, news breaks are “brought to you by” sponsors with political leanings, sports coverage is a mosaic of brand integrations. There's no pause. Content and advertising have merged into a single ecosystem.

Today’s media is shaped by sponsorship potential. The old cable promise—content without compromise—has been flipped on its head. Now, compromise is the model. Story arcs adapt to paid opportunities. Characters are brand tools. Creative freedom is budgeted alongside ad slots. Social platforms train creators from day one to monetize everything—anxiety becomes a journaling app, motherhood becomes diaper deals.

The shocker? We're paying to be advertised to. Hulu, Paramount+, even Netflix: all charge subscription fees and insert ads. It’s commercialized gaslighting: you pay, but then companies sell your attention again, and again. No wonder it feels awful. You’re both the customer and the product.

This is advertising’s quiet triumph—not a hostile takeover, but a slow integration. Ads stopped interrupting the story and began blending into it. Then they became the story. They’re not just part of the experience now—they are the experience. We didn’t fight it. We got used to it. We traded control for ease, and called it progress.

We scarcely notice anymore. Ads are in the plot, the jokes, the scroll. Storytellers paused mid-tale to pitch, sold stories about how good the story should make products look. We didn’t resist. We surrendered.

We didn’t just tolerate this. We were seduced. Not bullied. Not fooled. We let it happen because it was easy—because autoplay was smoother than resistance. We accepted ads stitched into everything we watch, listen to, scroll past, and pay for. We bought convenience and sold off the rest.

And now, most of us pay rent.

Maybe the only solution is a strike. A weeklong rebellion. Dust off the old DVD player. Pull out the silver discs in their cracked cases—the ones that don’t buffer, update, or track you. Watch The West Wing without a VPN pitch. Revisit Blade Runner without five mid-rolls. No Hulu, no YouTube, no “skip ad in 5 seconds.” Just content—whole, uninterrupted, and ad-free.

It won’t fix the system. But it might remind us we had a choice.