The Dunning-Kruger Republic

Joe Zeigler

Summary: The Founders built a republic, not a democracy. They didn't trust the public, so they created guardrails—an appointed Senate, an Electoral College as filter, restricted voting. We tore them down. The Dunning-Kruger voter—certain of what he doesn't know—got sovereign power. Democrats abandoned the working class; Republicans picked them up with grievance, not policy. Make a man feel superior to immigrants, to the educated, to the coasts, and he won't notice his pocket being picked. He'll vote for more. The cruelty is the point. The Founders feared Caesar and the mob. We gave them both.

I voted Republican for decades. Built three companies from scratch, never took a handout, believed every word about bootstraps and personal responsibility. I was exactly who they claimed to represent. Then I started paying attention to what the party actually did—not the speeches, not the slogans, but the votes, the money, the people they protected. And I realized I'd been conned. We all had.

Then came PrumpTutin, and the ride was truly over.

The Founders—every single one a man—built a republic, not a democracy. Franklin's quip, "a republic, if you can keep it," wasn't a joke. It was a warning. They created three branches—legislative, executive, judicial—because they didn't trust any human being with too much power. A Senate appointed by state legislatures, not elected by the people—that lasted until the 17th Amendment in 1913. An Electoral College designed to be a brake on populist madness, not a rubber stamp but a filter. Voting restricted to white male property owners. The Founders didn't hide their distrust. They wrote it into the structure. They'd read their Roman history. They didn't want Caesar. They didn't want the mob.

The early republic was a cage built around fear—fear of tyranny, fear of mobs, fear of ignorance, fear of concentrated power, fear of unrestrained democracy. They expected the public to be fallible. They expected the public to be temptable. They expected that one day someone would come along and turn ignorance into power. They built guardrails and hoped they'd hold.

They taught us something different. In high school, we were told we lived in a democracy. Teachers repeated it without thinking. Civics classes used the word as if it were gospel. No one corrected it in college. It became an American superstition: if you said "democracy" often enough, it might become true. So liberals set out to expand participation. More polling places. Mail-in ballots. Easier registration. We wanted everyone to vote. It was righteous. It was fair. It was modern. We believed all three. We ignored the Founders' fear because we assumed the species had matured.

Except it hadn't.

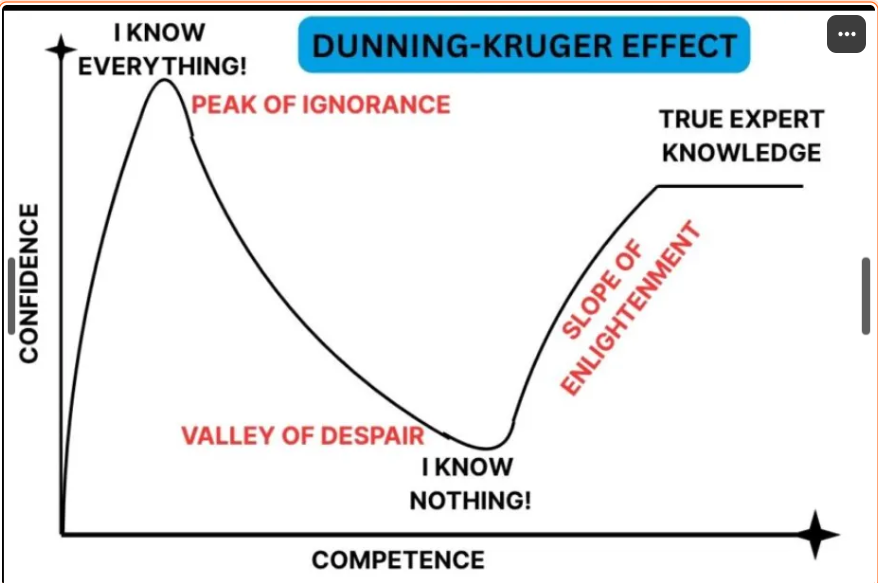

The result was exactly what the Founders feared. The Dunning-Kruger voter—the citizen most certain of what he doesn't know—got sovereign power. Certainty without knowledge. That's what we built our system around. Millions now vote against their own interests because they don't understand their interests. They vote for men who promise to destroy the government because they don't understand what government does. They believe fantasies because fantasies make them feel wise. They're not evil. They're confident.

They aren't alone in their anger. Forty years of wealth concentration gutted the middle class. Productivity rose. Wages didn't. The rich won the lottery and everyone else watched. That rage is real.