The Solution to Capitalism

The Beach Is Right There A sequel to "Capitalism Doesn't Work"

Ms Arthur asked for solutions for Capitalism is not Working. Fair enough. Complaining without offering alternatives is just whining with footnotes.

Summary

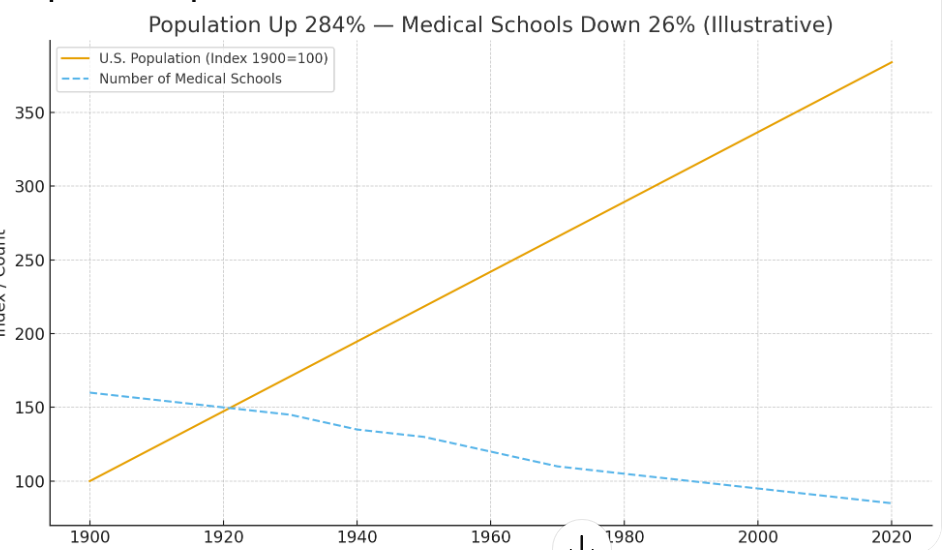

The solutions to capitalism's failures aren't complicated—they're obvious. Universal basic income, twenty-hour work weeks, wealth caps, public ownership of natural monopolies, debt jubilee. Every one has been tested somewhere and works. Alaska's had UBI for forty years. Germany's at 28 hours. Norway taxes wealth. The AMA restricted doctor supply for a century—population up 284 percent, medical schools down 26 percent—manufacturing scarcity while people died waiting. Smart people screwing us without mercy. We won't implement solutions because they'd transfer power from capital to labor and admit the ideology failed.

The beach is right there. We're not allowed to go.

The solutions aren't complicated. They're obvious. We won't implement them—not because they don't work, but because they work too well. They'd redistribute power along with wealth. They'd admit capitalism failed. They'd end the leverage capital has over labor.

Capital means ownership—stocks, property, machines. The stuff that makes money while you sleep. Labor means work—the stuff that makes money while you're awake. The war between them is the oldest story in economics, and capital is winning.

Paul Krugman—Nobel laureate, the economist who actually gets it—put it simply: "We have this long period, this long, flat stretch of a pretty equal society. That's the America I grew up in. Then woof, it takes off, starting in the late 70s... more and more of the income gets concentrated in the hands of a few people." The diagnosis is clear. So is the prescription. Krugman has spent decades explaining that government spending doesn't automatically cause inflation—not when there's slack in the economy, not when millions are unemployed and factories sit idle. The restraint isn't moral. It's mathematical.

But you asked for solutions, so here they are.

Universal basic income. Not welfare. Not charity. A dividend on collective productivity. When machines do the work, everyone gets a share. This isn't socialism—it's capitalism that finally acknowledges who creates value. Even Milton Friedman understood this. In 1962, the godfather of free-market economics proposed a negative income tax—functionally identical to UBI—because he recognized that markets can't distribute abundance. Over 1,200 economists signed a petition supporting it. Friedman wanted to replace the welfare bureaucracy with direct cash payments. He was right about the mechanics, wrong about replacing all other programs. But the principle stands: give people money, let them decide how to spend it.

Alaska's been doing it for forty years. Every resident gets $1,600 annually from oil revenues. Republicans run the state. Nobody calls it socialism. Society didn't collapse. People didn't stop working. They just stopped taking desperation jobs.

At $1,000 monthly per adult, UBI costs $3 trillion annually. Sounds impossible until you remember the Fed created $9 trillion since 2008 just to inflate asset prices. We have the money. We're giving it to the wrong people.

Finland ran UBI trials. People didn't stop working—they stopped doing pointless work. Spain launched a guaranteed minimum income during COVID—means-tested, not universal, but still running in 2025 with two million recipients. Kenya's running the world's largest UBI experiment. Results are uniformly positive. Employment stays stable. Mental health improves. Entrepreneurship increases. The fear that people will become lazy if you give them money? Exposed as projection by people who've never been poor. Poverty is exhausting. Remove the exhaustion, people do more, not less.

Twenty-hour work week. In 1930, John Maynard Keynes predicted that by now we'd be working fifteen hours a week. He wrote that technological progress would make it possible, that "three hours a day is quite enough to satisfy the old Adam in most of us." He was right about productivity—we're twice as productive as he imagined. He was wrong about our willingness to let workers share the gains.

Here's where the logic breaks down. We solved production. Technology did what it was supposed to do—made more stuff with less effort. Productivity doubled, then doubled again. We can feed ten billion people, house everyone, generate more electricity than we use. The machines won. So why aren't we at the beach?

Because the system can't process the answer. Capitalism needs scarcity to function. Prices need scarcity. Profits need scarcity. Employment as distribution needs scarcity. When you solve production, you don't get leisure—you get a system thrashing to maintain artificial scarcity so the mechanisms don't collapse.

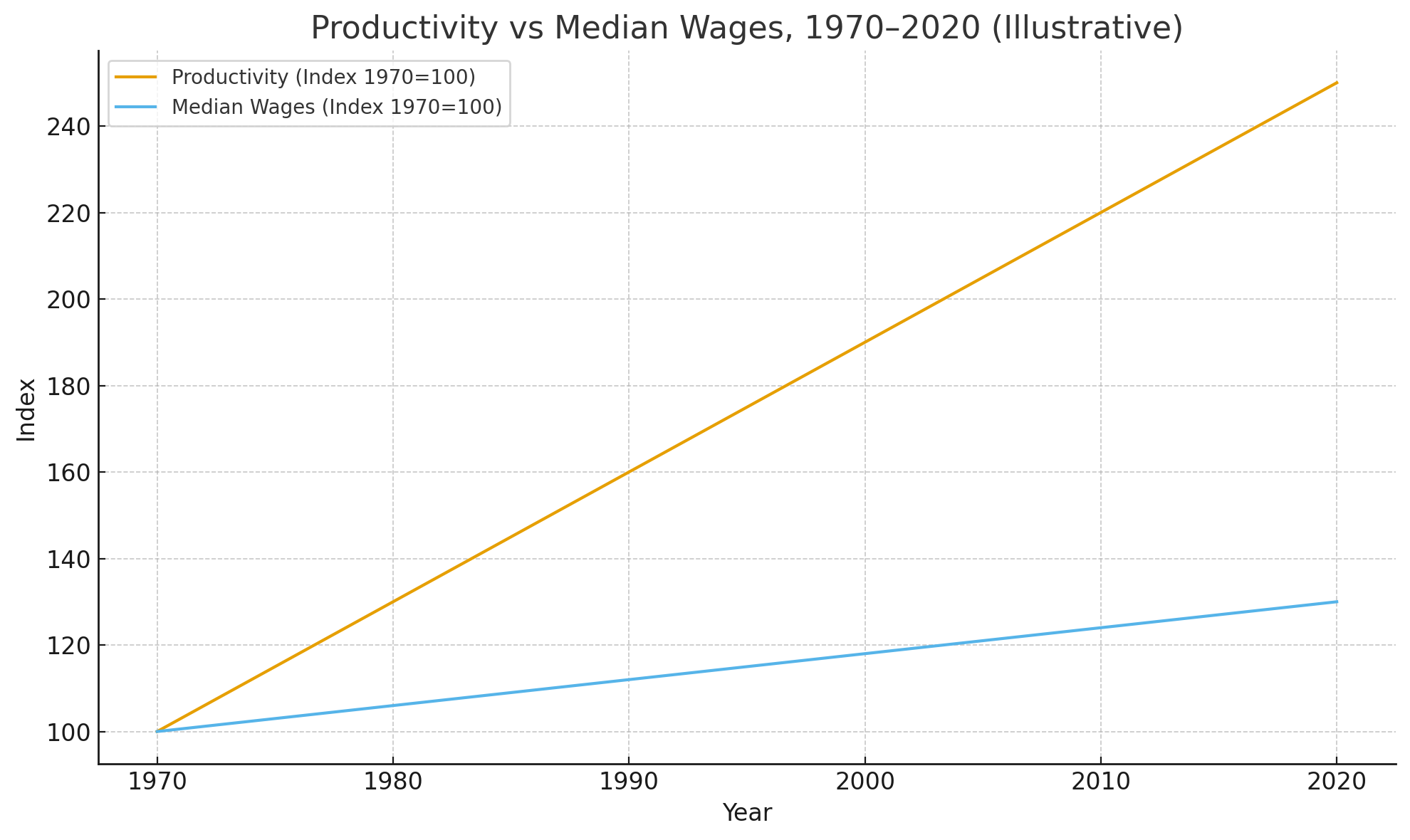

The productivity gains went somewhere. They went to capital. Every hour of increased output that should have bought workers an hour of freedom instead bought shareholders another yacht. The math is simple: if we're twice as productive, we could work half the hours for the same output. Or we could work the same hours and split the surplus. We did neither. Capital took it all.

Keynes assumed the gains would be shared because he couldn't imagine a system so captured by ownership that it would rather destroy abundance than distribute it. He thought we'd choose leisure. He didn't account for the fact that we don't get to choose—the people who own the machines choose. And they chose more for themselves.

The beach was always possible. The technology delivered. What failed was the distribution mechanism—an economic system that literally cannot say "enough" because enough means the end of growth, and the end of growth means the end of returns on capital, and the end of returns on capital means the ownership class loses its reason for existing.

So we work. Not because the work needs doing. Because the system needs us to need jobs to survive, and it needs us desperate enough to accept whatever jobs exist, no matter how pointless. The meaningless jobs aren't a bug. They're the patch that keeps the whole thing from crashing.

The beach is right there. Has been for decades. We're not allowed to go.

The market fundamentalists have an answer: price signals coordinate complexity better than any central planner could. They're not wrong about that. But price signals assume scarcity. When scarcity disappears, so does the signal. You can't price abundance—you can only destroy it or give it away. We chose destroy.

France proves 35 hours works. Netherlands averages 29 hours with higher productivity than the United States. Germany's IG Metall union won a 28-hour option for workers back in 2018. The math works everywhere it's tried.

The choice is simple: full employment at 20 hours, or half employment at 40 hours doing mostly nothing. We chose the cruelest option—full employment at 40 hours where half the work is theater. Spread necessary labor across more people. Everyone works less. Everyone has income. Productivity stays constant. The only thing lost is the desperation that keeps workers compliant.

Wealth caps. No one needs a billion dollars. No one can spend a billion dollars. It's not wealth at that point—it's scorekeeping for sociopaths. Thomas Piketty put it plainly: "Wealth is so concentrated that a large segment of society is virtually unaware of its existence." His research proved what anyone paying attention already knew—when the return on capital exceeds economic growth, the rich get richer automatically, without labor, without innovation, without adding anything. The past devours the future.

Cap wealth at 1,000 times median income. In the United States, that's roughly $70 million. Still rich enough for yachts, private jets, multiple homes. Not rich enough to buy senators, fund propaganda networks, or purchase democracy wholesale. When you've won that much, you've won. Take a victory lap. Let someone else play. The Gilded Age ended with trust-busting and progressive taxation. We've been here before. We know how to fix concentrated wealth. We just forgot we're allowed to.

Public ownership of natural monopolies. When marginal cost approaches zero—electricity, water, internet, healthcare—private ownership makes no sense. These become natural monopolies that require artificial scarcity to function profitably.

Power grids, water systems, internet backbone—when everyone needs it and competition's impossible, profit is theft. Run them at cost. Distribute at marginal cost. No shareholders demanding returns on abundance.

This isn't radical. It's how we handled utilities for most of American history. We privatized them because ideologues convinced us markets solve everything. Markets solve allocation problems. Infrastructure isn't an allocation problem—it's a distribution problem.

Price controls on surplus essentials. If we have surplus food, housing, medicine, energy—cap prices at cost plus reasonable margin. No more $300 insulin that costs $3 to make. No more $2,000 rent for apartments that cost $400 to maintain. No more empty houses appreciating while people sleep outside.

Not Soviet price controls on everything. Targeted controls on demonstrated surplus. When abundance exists, charging monopoly prices for access is theft. We already do this with water in most cities. We already do it with electricity in some states. Extend the principle to everything we have too much of.

Debt jubilee. Ancient civilizations understood what we've forgotten: when debt becomes unpayable, you forgive it or face revolution. Student loans, medical debt, underwater mortgages—wipe them clean. The money was created from nothing anyway. It can return to nothing. Every thirty years or so, the Babylonians declared debt jubilee. Slaves went free. Debts were cancelled. Society reset. They did this because they understood compound interest eventually consumes everything. We've forgotten. We'll remember.

Together, these tools create an economy that can process surplus instead of destroying it. Not socialism. Mechanics. Using tools that match the environment.

We've seen this pattern of backwardness before. We're seeing it now with healthcare.

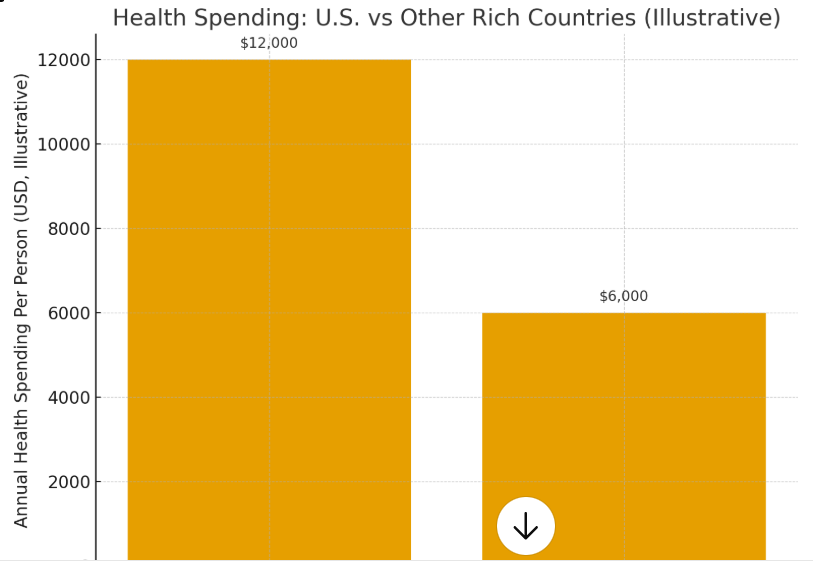

Every developed nation on earth has universal coverage. Every one. Germany, France, Japan, Canada, Australia, Taiwan, South Korea—even countries we bombed into rubble rebuilt with universal healthcare. They spend half what we do and live longer. Their citizens don't go bankrupt from cancer. Their diabetics don't ration insulin. Their mothers don't die in childbirth at third-world rates. We know the solutions work. We have fifty years of data from thirty countries. The evidence isn't ambiguous.

And yet we remain the only developed nation where medical debt is the leading cause of bankruptcy. The only one where insurance depends on employment—which means losing your job when you get sick costs you coverage exactly when you need it. The only one where an ambulance ride can cost more than a used car.

The scarcity isn't accidental. It's policy. Designed by people smarter than us, implemented without mercy.

In 1904, the American Medical Association created its Council on Medical Education with one goal: shut down medical schools. They couldn't say that publicly—too obvious a self-interest charge—so they funded the 1910 Flexner Report through the Carnegie Foundation. Carnegie was invulnerable to accusations of self-interest. The AMA wasn't. Same agenda, different letterhead.

It worked. Since the AMA began its campaign, the population of the United States has increased 284 percent. The number of medical schools has declined 26 percent. They called it raising standards. Economists call it restricting supply. The rest of us call it what it is: rigging the game.

They kept at it. In 1997, the AMA lobbied Congress to cap residencies, warning of an imminent physician "glut." They successfully convinced Medicare to limit how many residents hospitals could train. The result? A projected shortage of up to 121,900 physicians by 2032. The same organization now wringing its hands about doctor shortages engineered those shortages.

Let that sink in. They restricted the supply of doctors. For money. While people died waiting.

That's not incompetence. That's calculation. Smart people—lawyers, lobbyists, association executives—sat in rooms and decided that physician income mattered more than physician availability. That your wait time, your rationed care, your medical bankruptcy was an acceptable price for their members' third homes. They knew the math. They did it anyway.

And they're still at it—lobbying against letting nurse practitioners and physician assistants perform basic care without physician supervision. Protecting the guild, not the patient.

This is what artificial scarcity looks like when the people creating it are smarter than the people dying from it. We solved the production of doctors the same way we solved the production of food and housing. Then we capped supply to keep the prices high and the desperation constant.

Why? Because admitting the solution works means admitting the ideology failed. It means insurance companies lose their rake. Hospital systems lose their markups. Pharmaceutical companies lose their pricing power. And politicians lose their donations.

The economic question is identical. Every solution I've listed has been tested somewhere. UBI works in Alaska and Finland. Shorter work weeks work in Germany and Netherlands. Wealth taxes work in Norway. Public utilities work everywhere they're tried. We don't lack evidence. We lack the will to accept it.

Healthcare backwardness and economic backwardness share the same root: an ideology that would rather watch people die than admit it was wrong. We let insulin cost $300 because free markets. We let houses sit empty because property rights. We let productivity gains flow entirely to capital because that's just how capitalism works. It isn't how it has to work. It's how we've chosen to let it work. The same country that can't figure out healthcare can't figure out distribution. Same disease, different organ.

So why won't we do any of it? Because every solution transfers power from capital to labor. Every solution admits the Protestant work ethic is a death cult in a world that doesn't need most work. Every solution challenges the core mythology that suffering creates value.

The Fed will keep printing money to inflate assets while wages stagnate. We'll keep inventing work that doesn't need doing. Keep destroying surplus. Keep pretending scarcity exists. Because the alternative requires admitting the game is rigged—and admitting you've wasted your life playing a rigged game is harder than watching it grind everyone else to powder.

The solutions exist. The pilots prove it. Other countries are already implementing pieces.

We won't. Not because it's impossible. Because it's easier to watch it burn than admit we were wrong.

Until the pain of pretending outweighs the panic of changing, we'll waste human lives to maintain prices. We'll burn abundance to protect a theory. We'll hold onto a dead economic model like it's a religion.

The surplus is here. The tools exist. The evidence is in.

The only thing missing is permission to stop pretending.

For Virginia Arthur, who asked the right question